|

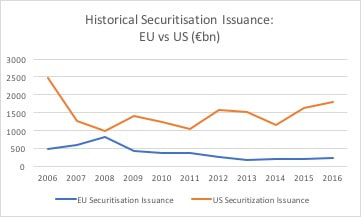

The chart above shows the evolution of securitisation issuance in the EU compared with that of the US over the last decade. US securitisation issuance suffered severely in 2007 and 2008 following the US sub-prime mortgage scandals together with the abusive use of US securitisation in that debacle. Since then, US securitisation issuance has established a generally upward trend and the latest figures suggest that this trend will be maintained in 2017. With more than two trillion dollars of annual issuance, securitisation is an important driver of US economic growth.

On the other hand, despite extremely low default levels in EU securitisation structures during the financial crisis, the regulatory backlash in Europe was both harsh and complex. European issuance remained low as banks were unable to overcome the burden of increased capital charges and other restrictions on securitised assets. The resultant impact on the European economy is reflected in substantially reduced levels of liquidity and investment, sharply limiting the ability of banks to re-size balance sheets, improve capital ratios and resume lending to businesses of all sizes. It has taken more than a decade for the EU to finalise proposals to rebalance capital charges for qualifying securitised instruments in an effort to revive the EU securitisation market. The new regulatory framework will apply to Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS) securitisation transactions. However, the STS regulation will not be implemented until 2019 and many doubt that it will generate a dramatic boost to issuance given the narrowness of the criteria and the complexity of the regulation.

0 Comments

Look forward to discussing how to optimise the management of Irish aviation leasing SPVs with you at the Airline Economics Conference next week. The event will be held at the Shelbourne Hotel, Dublin from 15 to 18 January 2017

Kieran Desmond, Managing Director, QSV Group [email protected] QSV Group is delighted to announce new services to support IP migration and the relocation of UK financial services firms to Ireland following the Brexit referendum outcome in June 2016. For more information, please see the following website pages:

A few large corporate services providers tend to win the bulk of new SPV management opportunities related to securitisation and structured finance. However, size is not directly correlated with quality. Private-equity backed corporate services providers aim to make money as quickly as possible at the highest possible margins. Unsurprisingly, the persistent pressure to lower costs leads to providers focusing on delivering minimum acceptable service levels at the lowest possible costs. The first symptom of a developing problem is often a high level of staff turnover at the corporate services provider, as over-burdened, underpaid employees search for more rewarding careers elsewhere. This leads to inexperienced staff being assigned to complex SPV structures and a gradual downward spiral of deteriorating service levels, higher error rates and lower customer satisfaction levels. Smaller, independent service providers, if carefully selected, can offer the best combination of quality, service and value. Before selecting a corporate services provider for a future SPV transaction, it is a good idea to check the skills, experience of those who will be acting as SPV directors and to be satisfied that there is an unequivocal commitment from senior management to delivering consistently high levels of quality, service and value. It is also a good idea to diversify the choice of service providers to enable service levels to be dynamically compared. Where a provider of corporate services fails to meet the required delivery standards, the transaction sponsor or originator, acting in conjunction with the Trustee, can usually arrange for a replacement to be made without incurring any significant costs. In a Strasbourg speech on 21 November 2016, Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, urged the European Parliament to end regulatory uncertainty and bring its deliberations on proposals to introduce a ‘Simple, Transparent, and Standardised’ (STS) securitsation framework to a conclusion. He said:

“In particular, the negotiations concerning the securitisation regulation need to be finalised soon. Securitisation can play a very important role in increasing bank funding to the economy but regulatory uncertainty is detrimental to European securitisation markets. We consider that the Commission has put forward a strong package that balances a revival of the European securitisation markets with the preservation of a prudent regulatory framework.” The European Commission put forward proposals to promote 'simple, transparent and standardised' (STS) securitisation in September 2015. The main objectives were:

However, the European Parliament has taken a full year to review these urgently needed changes and will not vote on the issue until mid-December 2016 at the earliest. Ireland's Finance Bill 2016, which was published on 20 October, clarifies the nature of proposed changes to Ireland's Section 110 regime. While measures are being introduced by the Irish government to tax gains on 'specified' mortgages, CMBS, RMBS and CLO securitisations will not be affected. Loan origination related to real estate will also not be impacted. The Minister of Finance, Michael Noonan, also reiterated his support for the Irish securitisation regime in his recent Budget speech.

Securitisations involve the acquisition of financial assets financed by the issuance of bonds. Unlike AIFS and UCITs, which are equity-based structures, securitisations are debt-based.

The shares of a Section 110 securitisation SPV always have little intrinsic value as essentially all of the proceeds generated from the acquired financial assets are returned to the bondholders under the terms of the bonds/notes. Nevertheless, a small pre-determined amount of the ‘profits’ will always be retained by the SPV as a corporate benefit. What do we do then with the SPV’s shares? In considering how to structure the ownership of an SPV, it is important that the SPV’s shareholders should be fully independent from the originator in the securitisation to reduce the risk of substantive consolidation. In addition, SPV shareholders should not create a risk that the SPV could be drawn into a shareholder’s own bankruptcy. Finally, it is important that the SPV shareholders do not take any action to wind up the SPV or try to engage it in other activities. Achieving these goals is not that straightforward. The market-standard SPV ownership solution emerged in the UK many years ago, whereby SPVs are established as ‘orphan’ entities whose shares are held by a trustee on charitable trust. This means that the nominal value realised by the SPV’s shares on winding-up will be paid to a registered charity, such as the Red Cross. Securitisations are not charitable ventures and while any financial benefit that might accrue to charities from the winding up of SPVs seems like something positive, this technical, risk-mitigating solution to the SPV ownership problem frequently creates confusion for the general public. While it is also possible to create non-charitable share trusts, why deprive charities of any source of funds? Over the last two decades, Ireland has successfully established itself as one of the leading tax neutral locations for qualifying fund entities, whether equity-based (UCITS and AIFs) or debt-based (Section 110 SPVs/securitisations). Why are funds granted tax neutral treatment in Ireland and many other countries? One of the accepted international tax principles is that investing through collective investment vehicles should place investors in the same tax situation as if they had invested directly in the underlying assets.

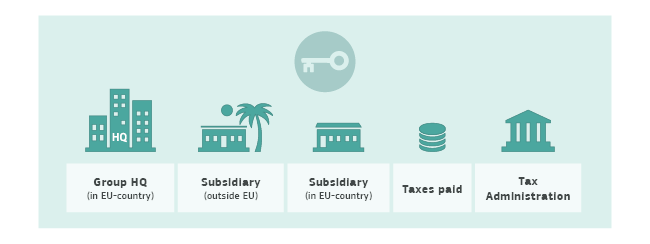

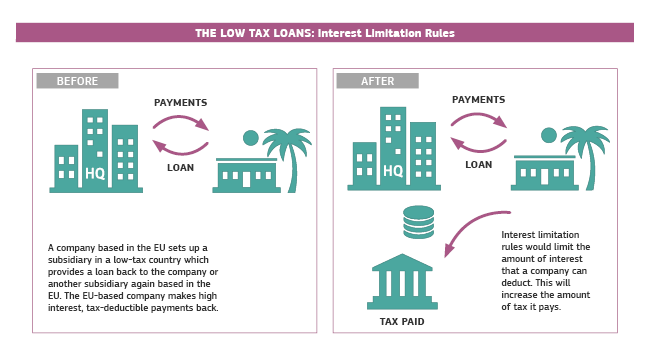

Securitisation is a vital source of finance for banks, enabling them to strengthen their balance sheets and increase lending to individuals and businesses, and the entire economy benefits from increased investment. Compared with The Netherlands, Luxembourg and other countries, Ireland was a little slow in introducing comprehensive legislation to facilitate securitisation. A brief chronology of securitisation developments in Ireland is presented below: 1991: Section 31 of the Finance Act permits securitisation of domestic mortgages by Irish banks and building societies. 1995: Ulysses Securitisation Plc, created in November 1995 for the purpose of securitising Irish local authority mortgages, was the first securitisation listed on the Irish Stock Exchange. The two bond issues in 1995 and 1996, totalling IR£190 million matured in 2006. 1996: The Finance Act facilitated the securitisation of international assets via SPVs located in the IFSC. 1997: Section 110 of the Taxes Consolidation Act set out eligibility criteria for qualifying SPVs. 1999: Section 110 eligibility extended to a wide range of financial assets. 2003: Further clarification of various taxation issues in relation to securitisation. Asset eligibility increased to permit, inter alia, synthetic transactions. A minimum €10m initial transaction threshold was introduced and non-IFSC-located SPVs were placed on an equal footing with IFSC-located SPVs. 2006: Private Irish companies, as well as public companies, could now be used in Irish securitisations, subject to certain conditions. 2008: Irish Section 110 SPVs permitted to acquire greenhouse gas emission allowances and insurance contracts. 2011: Qualifying Section 110 assets extended to include carbon offsets (replacing greenhouse gas emission allowances), commodities, plant and machinery. Five Key Areas to be Addressed by the Anti-Avoidance Tax Directive Adopted on 12 July 2016On 12 July 2016, the EU’s Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) formally adopted the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD) and it was subsequently published in the Official Journal of the European Union on 19 July 2016. This represents unanimous agreement from 28 countries on a set of five minimum implementing measures to tackle aggressive tax planning and other corporate tax avoidance strategies. For non-tax specialists and the public at large, these are esoteric adjustments that are difficult to interpret. However, the fiscal impact will affect everyone in the EU. The Directive attempts to address some of the most egregious international tax loopholes, while allowing individual EU countries to go further at national level, if they wish.

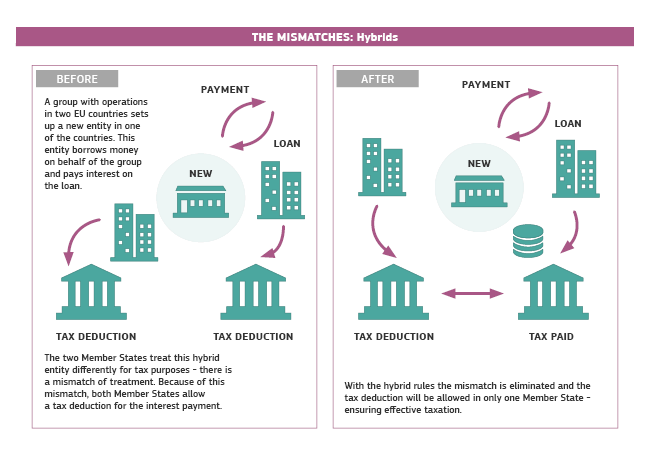

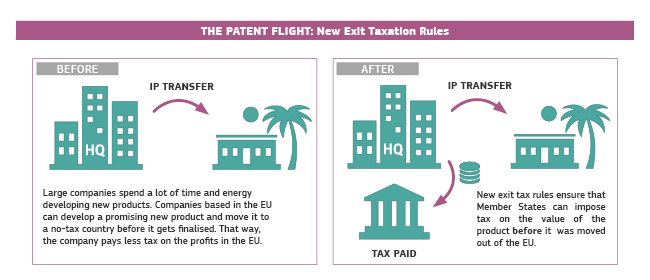

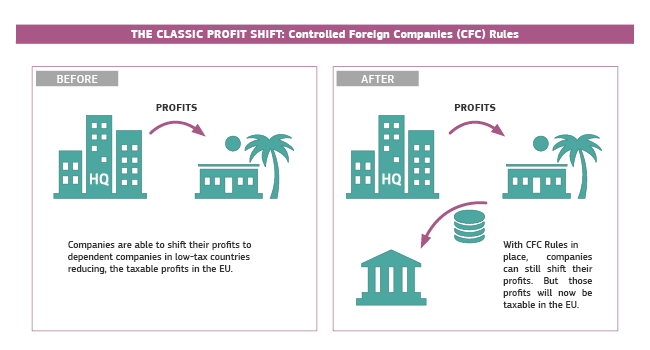

Hybrid mismatches (double interest deductions, etc) are tackled by the Directive. However, the provision only applies to hybrid mismatches within the EU. The number of situations where an EU entity would give rise to a hybrid mismatch benefit appears to be small and this type of mismatch would be subject to pre-existing EU control measures such as those contained in the EU Parent Subsidiary Directive. The ECOFIN has requested the European Commission to put forward a proposal relating to hybrid mismatches with non-EU countries by October 2016. New limitations on interest deductions may be deferred until as far away as 2024 for countries that already have strong targeted rules, and the EU Commission will determine which countries qualify for this type of deferred implementation. It seems likely that Ireland and Luxembourg will meet the criteria. The Netherlands also plans to tighten its own interest limitation rules before end-2016. Financial undertakings (financial institutions, insurance undertakings, UCITS, AIFs, etc) are temporarily excluded from the provisions of the Directive. The bulk of the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive will be in effect by the start of 2019, while the exit tax must apply from 2020. The Directive also contains grandfathering provisions for certain transactions already in place before June 2016. Some countries, such as the UK, will fast-track implementation as well as applying tighter unilateral controls. While the Directive will probably not have an enormous financial impact in the short-term, it is a truly momentous, if not revolutionary, first step from the EU in implementing the findings from the OECD’s BEPS project. The five key areas addressed by the Directive are summarised briefly below: 1. Hybrid mismatches This provision tackles cross-border arrangements that result in either (i) a double deduction or (ii) a deduction without inclusion by the other EU country. 2 Interest deductibility limitation The essence of the new rule is that excess borrowing costs will be deductible up to 30% of the company’s EBITDA or, optionally, up to a EUR 3m threshold. A grandfathering provision applies to loans concluded before 17 June 2016. As mentioned above, the new limitations on interest deductions may be deferred until 2024 for countries that already have strong targeted rules. Ultimately, the EU taxation impact of these interest limitation provisions should be substantial. 3. Exit taxation An exit tax will be applied to certain cross-border transfers of assets or residence within the EU or to a third country. For transfers within EU or EEA countries, the rule includes a tax deferral mechanism that allows companies to pay the tax in instalments over five years. Ireland, for example, already applies a broadly similar type of exit tax. 4. General Anti-Abuse Rule (GAAR) The GAAR is similar to that inserted in the EU Parent-Subsidiary Directive and tackles artificial tax arrangements (i.e. not based on valid commercial or economic reasons) where no other specific anti-avoidance rule applies; 5. Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) rule A CFC rule will apply if the corporate income tax paid by the CFC is lower than 40% of the tax that it would have been charged in the home/controlling jurisdiction. Under one of two implementation options, there is a carve-out for companies with substantive economic activity (staff, premises, equipment, assets, risk undertaken) and this is the route that Ireland will likely take as it is consistent with its longstanding inward investment strategy. The resignation of EU Financial Services Commissioner, Jonathan Hill, has dealt a serious blow to the prospects of restarting the European securitisation markets. His well-informed, moderate, pragmatic and common-sense approach offered a refreshing antidote to European pressures for ever-greater regulation and bureaucracy. Meanwhile, Paul Tang, the European Parliament Rapporteur that is responsible for taking Jonathan Hill's proposal for Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS) securitisations through the European Parliament, is considering making some rather draconian amendments to the text, including an increase in the risk retention requirement from 5% to 20%. When introducing severe post-crisis capital charges on securitisation positions held by banks and institutional investors, European regulators did not attach sufficient weight to the fact that legacy European securitisations performed exceptionally well during the crisis. Default rates remained at a fraction of 1% . The idea is that STS securitisations should benefit from reduced capital charges. The sub-prime securitisation debacle was an American problem that resulted in global contagion. The root of the problem was not the technique of securitisation per se (while acknowledging that the complexity and opacity of some structures was an exacerbating factor) but rather fraud, negligence and other criminal behaviours across the US banking system on an alarming scale. Major US banks have been fined more than $200 billion for misleading investors, including JP Morgan Chase $13bn, Bank of America $17bn, Citigroup $7bn, Goldman Sachs $5.1bn, Morgan Stanley $3.2bn, Wells Fargo $1.2bn. The SEC brought charges against more than 195 entities and individuals, including 89 CEOs, CFOs and other senior managers, that also resulted in billions of dollars of fines. In too many cases, the representations and warranties provided by US banks in relation to securitised sub-prime mortgages proved to be false and worthless. We should not punish European securitisations or the securitisation market as a whole for these outrageous US sub-prime excesses. The remarks made by Jonathan Hill in his recent (and last) presentation on securitisation to the European Parliament sum up the situation well. The text is reproduced below: ____________________________ Remarks of Commissioner Jonathan Hill at the European Parliament's Public Hearing on Securitisation Brussels, 13 June 2016 Thank you for the chance to come and talk about our proposals to restart securitisation markets. To explain why that's important if we want to help increase funding to the wider economy and to manage risk more effectively in our financial system. And to set out how we want to proceed in a way that's measured, prudent, and learns from the past. The Committee has of course given a lot of thought to this issue and I’m grateful for the recent reports of Paul Tang and Pablo Zalba, and for all their work on the Securitisation Regulation proposal and the CRR amending regulation. If we go back to the crisis, it's worth remembering that EU securitisations performed well. It was American ones that didn't. In response, we took action to strengthen our governance framework and ensured all securitisations in Europe are properly regulated. We've increased capital requirements; introduced rules on risk retention to make sure issuers have the right incentives; increased transparency; established due diligence requirements before investments are made; set clear standards and strengthened oversight. None of this is in question. But now, as we work to support investment, it's sensible to ask some questions. To make sure that we're not tarring an entire market with the same brush. And to look carefully at the body of analysis that points to the positive role securitisation can play in a modern economy. Why is securitisation important? Well, in their simplest form, securitisations can be straightforward and benefit the whole economy. By converting pools of individual loans into tradable bonds, they open up investment into households and businesses from a much wider market than just banks. In the financial sector, securitisation allows banks that receive monthly mortgage repayments to combine loans and offer them to investors who want a share of those repayments in return for their investment. It means banks can then raise further financing, reduce borrowing costs for consumers or support more lending to the wider economy. It gives investors access to investments that they might not be able to make directly themselves. But the importance of securitisation goes well beyond the financial sector. A car manufacturer receiving monthly payments from customers that have taken out car loans can sell its claim on those payments to finance research and development, and remain competitive. A department store with an in-house store-card might use securitisation to sell its claim on card repayments to support product development and improve its service. Or a company leasing specialised equipment could use securitisation to sell its claim on lease repayments to grow and expand into other markets. Securitisation helps companies diversify their funding sources across the board. And it's also an important way for banks to manage some of the risks they have to take to provide many of the services their customers depend on in their daily lives, like loans to buy a house or a car. How does this work? Well a securitisation is a transfer of assets – like mortgages or SME loans - to a vehicle which issues securities backed by these assets. Institutional investors can invest in these securities and the bank keeps some of them – a minimum of 5% – to ensure everyone’s got skin in the game. This shares risk more widely between the different parties in the financial system; it reduces the risk of shocks; and helps strengthen financial stability. Securitisation also provides more opportunities for investors, particularly institutional investors, like insurance or pension funds. Securitised assets are an attractive way for them to benefit from the steady return delivered by well-regulated consumer and corporate loans. The institutions which extend the loans often have specialist knowledge of the sector where the loans are granted. The institutional investors can benefit from this expertise and use securitisations to diversify their portfolio of assets for the benefit of their clients. At macro-level, securitisation can also support financial stability. The ECB and the Bank of England have argued in a joint paper that transferring some credit risk away from the banking sector can be beneficial to the wider economy, to the banking sector, and both monetary and financial stability. They're not alone. Today, there's a broad consensus among regulators, supervisors, and the companies that need the financial markets, that building stronger securitisation markets would be beneficial for the European economy. I agree with them. At the moment, issuance of securitised products in Europe is low. Issuance has dropped from nearly 600 billion euros in 2007 to under 220 billion in 2014. SME securitisations are half of the pre-crisis level. This means that risk is more concentrated, that there are fewer funding options, and fewer options for investors. That's why we came forward with a proposal to restart securitisation markets by defining Simple, Transparent and Standardised securitisations. These criteria build on work done by the Basel Committee and IOSCO. We've used the work and analysis by the ECB, the Bank of England, the ESAs' Joint Committee, and we've sought and received valuable advice from the EBA. Our proposals flow from the solid analysis and cautious recommendations of these independent and respected institutions. They are based on the products that performed well during the crisis and exclude those that have failed. Our goal is to free up more lending for investment in the wider economy by creating a new category of securitisations, securitisations that fulfil very specific criteria of simplicity, transparency and standardisation, with appropriately calibrated capital requirements for those who invest in securitisations. So what do we mean by Simple, Transparent and Standardised? By Simple, we mean only securitisations that bring together loans that are comparable. So mixing mortgages with car loans is out. We mean securitisations that don't repackage other securitisations. And we mean securitisations where the securitised assets cannot be cherry picked to the advantage of the issuer. So repackaging non-performing loans is definitely out. To ensure these securitisations are Transparent, those selling securitised products will need to make the right information available to investors and regulators, so that they can undertake an assessment of risk and return, and developments in European securitisation markets can be monitored. Our proposals would make it compulsory for relevant information to be made available electronically to all investors free of charge, in a way that was clear and comparable. And to ensure proper oversight, we're proposing a framework to improve cooperation and coordination between the different national supervisors and the ESAs, to make sure the information flows, and everyone abides by the rules. I know that Verena Ross, from ESMA, will be speaking to you in a moment. ESMA will play a key role in ensuring the integrity of the overall framework. By focusing on Standardised securitisations, our intention is to identify securitisations that use consistent and well understood structures, where the issuer retains some of the assets that are being securitised, and where the obligations for all the parties involved are clear up front. Any assets in STS securitisations would have to be credit worthy according to the rules of the Mortgage Credit Directive and the Consumer Credit Directive. Put simply, the criteria for simple, transparent and standardised securitisation would help investors to understand what they're investing in. It would make the risk of the underlying assets easier to assess for professional investors. And it would empower investors by making them less reliant on the assessment of rating agencies, enabling them to make their own judgements based on reliable information. The criteria for STS have been set to make sure that we learn from the mistakes that led to the American sub-prime mortgage boom, and ensure they are not repeated in Europe. We’re right to keep the lessons of the crisis in our mind’s eye. But that should lead to caution, not inertia. Prudence, not paralysis. And it's worth remembering that European securitisations fared much better than American ones. The EU's worst performing AAA securitisation products’ default rate was 0.1% at the height of the crisis. In America, it was 16%, with the consequences we all know. So the case I'm making today is cautious but forward looking. It's for us to build on the post-crisis reforms. It's for an intelligent solution - based on the advice of independent international and European bodies – that will help us make the most of Europe’s well-managed securitisation markets. One that channels funding to the wider economy. My proposals for Simple, Transparent and Standardised securitisation do just that. They’ve been welcomed by Mario Draghi, who’s said “they achieve the balance between the need to revive Europe’s securitisation markets and the need to preserve a prudential regulatory framework.” They contain a robust supervision and sanctioning regime so that market participants live up to their responsibilities, and are held accountable through strong oversight. And at the same time, they deliver a more risk sensitive treatment and more straightforward legal framework, to make it easier to issue and invest in securitised assets. We know there's an investment gap in the European economy. And we know our businesses need more funding to grow and compete internationally. Simple, Transparent and Standardised securitisation can make a difference. It's an opportunity to combat the biggest macro threat to financial stability: the lack of growth itself. That's an opportunity I hope we can work together to seize, to move these proposals forward, to get them agreed, and by increasing funding sources and bank lending, to support growth in Europe. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-16-2188_fr.htm |

AuthorKieran Desmond Archives

December 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed